Economics in One Lesson Part 1

I actually read another book since finishing the Bitcoin Standard. I didn't feel like writing about it here, since it was a different kind of non-fiction. It is by my friend Ben Schilaty and it's called A Walk in My Shoes, about his experiences as a gay Latter-Day Saint. Some of it I'd already read from his blog, and some of the things I "learned" were spiritual and personal, meaningful to me because my testimony needed his testimony to buoy it up. Not exactly what this blog is for. But if anyone actually ever reads this, I do recommend Ben's book. I offered it up on my local Buy Nothing FB page when I was done and there are several going to pass the book around, so that was fun.

So now I'm onto Economics in One Lesson by Henry Hazlitt. The Mises Institute was shipping them to people for free, so I said, "Why not?"

The "one lesson" is taught right at the beginning, all other chapters offering different ways this lesson is forgotten or lacking. The lesson is this, are you ready?

"The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."

In the Bitcoin Standard, it was mentioned that, when asked about the long term consequences of his economic policies, Keynes responded that, "In the long term, we are all dead." Apparently, Keynes never learned, or never cared about, this one lesson.

In order to understand the long term consequences of any economic policy, one must be able to shelve the immediate benefits, or indeed negative consequences, and take time to ponder possibilities, alternatives and hypotheticals. Most people can't be bothered. This is not an indictment of their character, as I've never bothered much about it before, rather it's merely an observation of why bad economic policies are so easy to implement. A little immediate gratification for the masses that don't analyze macro economics, and those in charge can do what they want with little push back. I loved this line from Hazlitt, " The bad economists rationalize this intellectual debility and laziness by assuring the audience that it need not even attempt to follow the reasoning of judge it on its merits because it is only "classicism" or "laissez faire" or "capitalist apologetics" or whatever other term of abuse may happen to strike them as effective." It reminded me of the section of the Bitcoin Standard where most non-Keynesian economists serve only as controlled opposition, a caricature of the evils of a free market.

Chapter II: The Broken Window

In this story, a shop keeper has his widow broken by some hooligan. A pain, for sure, but hey! It created a job for the glazier! (Did you know that's what a glass working person is called? I didn't.) Huzzah, through this minor trouble, we have stimulated the economy! Now, if you are thinking to yourself that this is a stupid take on the shopkeeper's misfortune, they you weren't paying very close attention to the riots last year. I definitely heard people excuse away all the destruction in this way. But let's look at the economic stimulation from the broken window. The shopkeeper was ready to buy a new suit, but now his money will go to a new window. Had the window never been broken, he could have had the window and the suit. He still would have stimulated the economy by providing work to the tailor instead of the glazier, but now he has stimulated the economy but is left only with the window he already had, he is no better off.

Chapter III: The Blessings of Destruction

The broken window fallacy sounds obvious enough after that example, but it is prevalent. This chapter discusses a lot of this fallacy going around after World War II. I'm sure we've all heard that war is good for the economy, right? "In Europe, after World War II, they joyously counted the houses, the whole cities that had been leveled to the ground and that "had to be replaced." Of course, this was no great boon to the economy. They most clearly would have been better off had nothing been destroyed in the first place, then they could have expanded or improved instead of just working to regain their baseline. Some argued that the Germans and Japanese had a post war advantage over the Americans because their factories had been destroyed. They could now rebuild with the latest technology, making them more efficient and more profitable than American factories. The only problem with this argument is that there was nothing stopping Americans from destroying their own factories if it was truly in their own interest. "The wanton destruction of anything of real value is always a net loss, a misfortune, or a disaster, and whatever the offsetting considerations in a particular instance, can never be, on the net balance, a boon or a blessing." It reminds me of Biden bragging about the "fastest job growth in the nation's history" or some such. Yes, Biden, because first we destroyed a bunch of jobs. a quick drop off of unemployment is not really that impressive when you see that we're still far about the baseline.

Another note from this chapter before I move on, Hazlitt argues that supply and demand are merely two sides of the same coin. That a farmer's supply of wheat merely represents his demand for other goods. He doesn't want the wheat, he wants to sell it so he can have other things. I had never considered it in this way before and thought it was interesting. I'm not sure how that will apply in looking at specific supply and demand issues, just....interesting.

Chapter IV: Public Works Mean Taxes

This chapter starts with the line, "There is no more persistent and influential faith in the world today than the faith in government spending." Now, this book was written in 1946. So with today's government spending being what it is (insert panicked screaming) I'm not sure if I should say this is even truer today, or if some people are finally starting to lose this faith. We shall see.

The point of this chapter is that the government gives you nothing for "free." It's sure trying to right now, with the endless debt and money printing, but "such pleasant dreams in the past have always been shattered by national insolvency or a runaway inflation." The example the author gives in this chapter is a bridge being built. Before it is built, people might say that another bridge in this area isn't really necessary, but it will provide so many jobs! It will stimulate the economy! But the bridge costs $10 million dollars. If that money is obtained with tax dollars, that's $10 million dollars that the constituents could have spent on things they valued more than another bridge. They could have stimulated the economy in ways they saw as most beneficial to them. Some of them could have perhaps started or expanded a business, which would have also provided jobs, but in another sector. If that $10 million is obtained through debt and money printing, it will devalue the savings of the constituents, essentially taxing them of the value. But we see the men at work on the bridge. It is much more difficult to see the jobs that could have been created elsewhere, it's difficult to measure the opportunity cost. Then after the bridge is built, people like it. it looks nice and is convenient. They see it and they like it. Three cheers for government! But they again fail to see what could have been instead. This is not to say that bridges are bad and the government should never build them, it is only to say that everything the government does comes at a cost, a monetary cost to constituents and an opportunity cost of what else the government could be working on, and it is important to put in the effort to look at the parts of the equation that can't be seen.

Chapter V: Taxes Discourage Production

Basically, too much taxing discourages employers from hiring new people. It keeps their profits down so it keeps them from expanding. Some are kept from starting a business at all. "The larger the percentage of the national income taken by taxes the greater the deterrent to private production and employment. When the total tax burden grows beyond a bearable size, the problem of devising taxes that will not discourage and disrupt production becomes insoluble."

Chapter VI: Credit Diverts Production

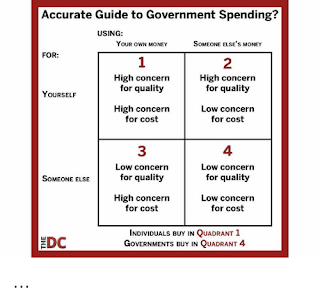

This chapter deals with something I don't really know much about, I wasn't really aware the government was involved in this, although it sort of makes sense now. I guess the government gives loans? I suppose this is just subsidizing things with an expectation of repayment. The problem here is the same problem with all government spending, illustrated here in this table based off Milton Friedman's writings.

When a private lender selects a farmer (the example used heavily in this chapter) to receive a loan, they have a vested personal interest in choosing the hardest working, one who will be most likely to see success and provide a return on investment. When the government gives out a loan (with money they took from you and which they can just get back from you), there is less incentive to vet the potential recipient. And, as was discussed previously, government spending on one farm/farmer means that another potential farm/farmer goes without said funding. In this way, production is reduced, because we have removed the free market forces that select for the most productive farmers. "When the government makes loans or subsidies to business, what it does is to tax successful private business in order to support unsuccessful private business." This plays into the main idea from the last chapter.

Comments

Post a Comment